Fixed asset depreciation determines how much tax you pay and how much cash stays in your business. Improper calculations cost you thousands in overpaid taxes or invite IRS audits that threaten your financial standing.

2025 brought major changes. Section 179 limits increased to $1,220,000 with a $3,050,000 phase-out threshold, while bonus depreciation fell to 40% for qualified property. State regulations continue separating from federal standards, creating compliance challenges for multi-state operations.

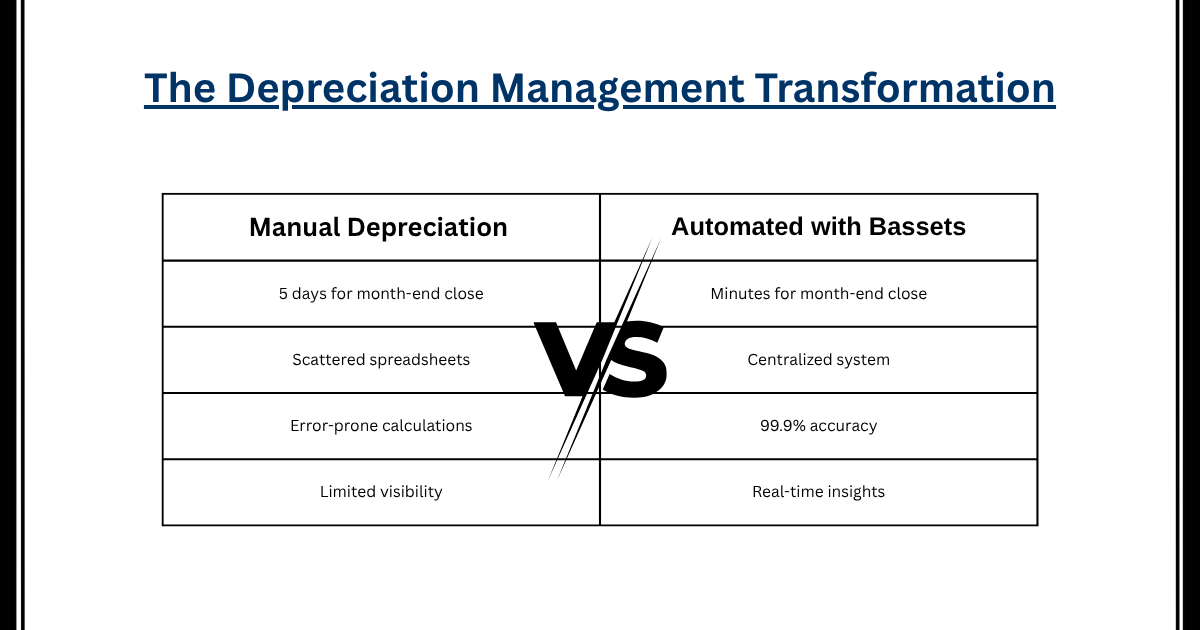

Manual tracking systems fail under this complexity. Finance teams using spreadsheets miss legitimate deductions averaging $15,000 to $50,000 annually for mid-sized organizations.

This guide shows you how to capture every available deduction while maintaining compliance.

You'll learn:

- Which methods generate the largest deductions for your asset types

- How to classify property under MACRS without triggering scrutiny

- When accelerated approaches beat straight-line calculations.

Already know the basics? Jump straight to “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation.”

What is Fixed Asset Depreciation?

Fixed asset depreciation allocates tangible property costs over useful life periods. This accounting method matches asset expenses to the periods benefiting from asset use, creating accurate financial statements while generating tax deductions that reduce taxable income without cash outflow.

Understanding depreciation methods and calculation requirements determines whether organizations capture every available tax deduction while maintaining financial statement accuracy that withstands audit scrutiny. The strategic application of depreciation rules transforms a compliance obligation into a powerful tax optimization tool.

Understanding Asset Depreciation Basics

Fixed asset depreciation spreads capital expenditure costs across multiple accounting periods instead of expensing entire purchase amounts immediately. When a business purchases delivery trucks for $50,000, depreciation accounting allocates that cost over five to seven years matching the vehicle's service life. Each year recognizes a depreciation expense portion.

The matching principle drives depreciation accounting under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. Revenue generated by fixed assets should align with expenses incurred producing that revenue.

Manufacturing equipment producing goods sold across multiple years depreciates over those years, ensuring income statements reflect true period-by-period profitability.

Tax depreciation follows different logic than financial reporting depreciation. The IRS uses depreciation to incentivize capital investment and economic activity through the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System.

Accelerated depreciation methods allow businesses to deduct costs faster than economic consumption occurs. Organizations maintain separate depreciation schedules for financial reporting and tax purposes.

Three factors determine depreciation calculations: cost basis, useful life, and salvage value. Cost basis includes purchase price plus capitalized costs. Useful life represents the service period duration. Salvage value estimates expected recovery value at disposal. Changing any input factor alters annual depreciation expense amounts significantly.

Why Depreciation Matters for Your Business

Depreciation expense reduces taxable income without requiring cash outlay during depreciation periods. Businesses spend money during asset acquisition, but depreciation deductions spread that investment across subsequent years.

This timing difference lowers tax bills and improves cash flow substantially. Capital-intensive businesses generate depreciation deductions exceeding hundreds of thousands annually.

Financial statement users rely on depreciation to assess asset base quality and capital efficiency. Investors and lenders analyze accumulated depreciation ratios to understand asset age and replacement timing requirements. High accumulated depreciation relative to gross fixed asset values signals aging infrastructure requiring capital infusion soon.

Budget planning and financial forecasting depend on accurate depreciation tracking. Planning equipment purchases requires knowing which assets reach end-of-life and need replacement. Depreciation schedules provide this visibility clearly. Organizations maintaining detailed fixed asset registers with depreciation tracking forecast capital needs three to five years forward.

Audit compliance requires defendable depreciation calculations and consistent application of depreciation policies. External auditors test fixed asset balances, useful life assumptions, and depreciation methods annually. Inconsistent depreciation policy application triggers audit adjustments and qualified opinions that damage stakeholder confidence.

The Relationship Between Depreciation and Asset Management

Depreciation tracking forms the foundation of comprehensive fixed asset management systems. Organizations cannot optimize assets they don't measure accurately. Companies implementing robust depreciation systems gain visibility into total cost of ownership, enabling data-driven decisions about maintenance scheduling and replacement timing.

Asset management systems track more than depreciation calculations. They monitor asset location, custodian responsibility, maintenance history, warranty status, and insurance coverage details.

Depreciation remains the financial anchor connecting physical assets to accounting records accurately. When facilities teams move equipment between locations, asset management systems update location fields while maintaining depreciation continuity.

This integration prevents disconnects between physical asset reality and financial records. Items fully depreciated but still generating maintenance expenses (A.K.A. Ghost assets) waste organizational resources unnecessarily. Missing assets that are disposed physically but still depreciating in accounting records overstate expenses and create false tax deductions that invite IRS scrutiny.

Types of Depreciable Assets

Fixed asset depreciation applies to specific asset categories meeting IRS requirements. Understanding which assets depreciate, how they depreciate, and what assets cannot depreciate can prevent costly tax errors.

Tangible vs. Intangible Assets

Tangible fixed assets have physical form. Some examples are:

- Manufacturing equipment

- Office buildings

- Delivery vehicles

- Computers

- Furniture

Physical deterioration through use and time passage makes depreciation both economically real and accounting-mandated for tangible assets.

Intangible assets lack physical substance but provide long-term business value. Examples include:

- Patents

- Trademarks

- Customer lists

- Software licenses

Intangible assets undergo amortization rather than depreciation. The IRS treats certain intangibles differently under Section 197, establishing 15-year amortization periods for purchased intangibles regardless of actual useful life.

This distinction matters because depreciation methods available for tangible fixed assets don't apply to intangible assets. Businesses can use declining balance depreciation or units of production depreciation for machinery. Intangible assets generally require straight-line amortization with limited exceptions.

Common Examples of Depreciable Fixed Assets

Buildings and Improvements

Buildings and building improvements represent the largest depreciable assets for many organizations. Commercial real estate depreciates over 39 years for tax purposes under MACRS depreciation, while residential rental property uses 27.5-year depreciation schedules. These long recovery periods reflect IRS assumptions about building longevity.

Building improvements including HVAC systems, roofing, electrical upgrades may qualify for shorter 15-year or 20-year recovery periods. This creates opportunities for accelerated deductions through cost segregation studies breaking building costs into components with different depreciable lives. Cost segregation can accelerate hundreds of thousands in deductions for larger properties.

Manufacturing Equipment and Machinery

Manufacturing equipment and machinery drive production capacity in industrial operations. CNC machines, assembly lines, injection molding equipment, and industrial robotics typically fall into MACRS 7-year property class. This classification provides reasonable recovery periods matching typical equipment replacement cycles.

Specific machinery categories use different recovery periods based on industry-specific factors. Semiconductor manufacturing equipment qualifies for 5-year treatment reflecting rapid technology obsolescence. Certain food processing equipment receives 10-year or 15-year classification depending on specialized functionality and expected service life.

Vehicles and Transportation Equipment

Vehicles and transportation equipment include cars, trucks, vans, and specialized vehicles like forklifts and delivery trucks. Standard automobiles face luxury vehicle limitations capping annual depreciation deductions regardless of actual cost. These limitations prevent excessive deductions on high-priced luxury vehicles.

Heavy vehicles exceeding 6,000 pounds gross vehicle weight escape luxury limits, making SUVs and trucks popular business vehicle choices. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act modified luxury vehicle depreciation rules significantly, affecting optimal vehicle selection for tax purposes. Understanding these distinctions helps businesses make strategic vehicle purchasing decisions.

Computer Equipment and Technology

Computer equipment and technology depreciates rapidly both economically and for tax purposes. Desktop computers, servers, networking equipment, and peripherals generally qualify for 5-year MACRS treatment. Short recovery periods reflect how quickly technology becomes obsolete in modern business environments.

Organizations replacing computers every three to four years often fully depreciate equipment before disposal. This creates losses on retirement providing additional tax benefits beyond depreciation deductions. Technology replacement cycles align well with accelerated depreciation methods, maximizing tax benefits from rapid refresh strategies.

Furniture and Fixtures

Furniture and fixtures outfit office and retail spaces with necessary equipment. Desks, chairs, shelving, display cases, and decorative elements typically use 7-year MACRS recovery periods. This classification provides reasonable depreciation timelines for items experiencing moderate wear.

Retail displays and certain restaurant equipment may qualify for shorter 5-year treatment under specific circumstances. The distinction depends on whether items are permanently affixed to buildings or easily movable. This judgment requires documentation when tax positions face IRS examination, making proper classification critical.

Leasehold Improvements

Leasehold improvements present special depreciation considerations. When businesses rent space and make improvements, those costs depreciate over the shorter of improvement useful life or remaining lease term. Tax treatment differs from GAAP treatment in important ways requiring careful analysis.

Qualified improvement property placed in service after 2017 should have received 15-year treatment with bonus depreciation eligibility. Drafting errors initially left it in 39-year classification. The CARES Act corrected this retroactively, creating opportunities for amended returns claiming previously unavailable bonus depreciation on leasehold improvements.

Non-Depreciable Assets

Land never depreciates under both GAAP and IRS tax rules. The IRS position holds that land doesn't wear out, become obsolete, or get used up through business operations. When purchasing property, businesses must allocate total cost between land and buildings. Only building portions generate depreciation deductions.

Assets held for investment rather than business use don't qualify for depreciation deductions. Principal residences don't depreciate even though they experience wear and tear. Investment property held for appreciation without rental activity or business use generates no depreciation deduction.

Assets with useful lives under one year get expensed immediately rather than capitalized and depreciated. Small equipment purchases, tools, supplies, and minor acquisitions all fall below capitalization thresholds most organizations establish. Amounts under $2,500 typically expense immediately for both book and tax purposes under IRS safe harbor elections.

Key Factors in Calculating Depreciation

Accurate depreciation calculation requires three critical inputs:

- Cost basis

- Useful life

- Salvage value

These factors determine annual depreciation expense amounts, tax deduction timing, and financial statement accuracy.

Understanding how to properly determine each component ensures compliance with IRS depreciation rules while maximizing legitimate tax deductions.

Determining Asset Cost Basis

Asset cost basis includes all costs necessary to acquire an asset and prepare it for intended use. The purchase price represents only the starting point for cost basis calculation.

Businesses must capitalize additional costs meeting IRS requirements for inclusion on a depreciable basis.

Purchase price and acquisition costs form the foundation of cost basis. The invoice amount, negotiated price, or fair market value at acquisition establishes the initial basis. For assets purchased in arm's-length transactions, this amount is straightforward. For assets acquired through non-cash transactions, fair market value determines the basis.

Sales tax and use tax paid on asset purchases add to cost basis. Many organizations incorrectly expense these taxes immediately rather than capitalizing them into asset basis. This error reduces the depreciable basis and decreases lifetime tax deductions significantly. Multi-state operations must track sales tax by jurisdiction and capitalize amounts correctly.

Freight and shipping costs necessary to transport assets to business locations capitalize into cost basis. Delivery charges, freight fees, and transportation expenses all increase depreciable basis when directly attributable to specific asset acquisitions. Blanket freight charges covering multiple purchases require allocation to individual assets.

Installation and setup costs capitalize when required to make assets operational. Professional installation fees, contractor charges for equipment setup, and employee time spent on installation all add to cost basis. Testing costs ensuring proper operation also capitalize into depreciable basis. Ongoing maintenance and repair costs expense currently rather than capitalizing.

Site preparation and modification costs that benefit specific assets capitalize into those assets' basis. Electrical upgrades for new equipment, reinforced flooring for heavy machinery, and facility modifications enabling asset use all increase cost basis. General improvements benefiting the entire facility depreciate separately as building improvements.

Estimating Useful Life

Useful life represents the period over which an asset provides economic benefit to the business. GAAP allows businesses to estimate useful life based on expected usage patterns, technological obsolescence, and physical deterioration. Tax depreciation uses IRS-mandated recovery periods from MACRS property classifications.

GAAP useful life estimation considers multiple factors affecting how long assets serve business operations. Expected usage patterns, historical experience with similar assets, manufacturer specifications, and industry norms all inform useful life estimates.

Physical wear and tear from normal operations shortens useful life measurably. Manufacturing equipment running multiple shifts experiences faster deterioration than single-shift operations. Usage intensity directly impacts appropriate useful life estimates.

Technological obsolescence affects useful life independent of physical condition. Computer equipment becomes outdated through technology advancement rather than physical failure. Software platforms require upgrading before hardware stops functioning completely..

Calculating Salvage Value

Salvage value represents the estimated amount recoverable when disposing of a fully depreciated asset. This residual value reduces total depreciable basis under GAAP depreciation methods. The difference between cost basis and salvage value determines total depreciation recognized over asset useful life.

Here's a practical example to illustrate salvage value:

Example: Company Delivery Truck

A company purchases a delivery truck for $50,000 with the following estimates:

- Useful life: 5 years

- Estimated salvage value: $8,000

Calculating Depreciation:

The depreciable basis (the amount to be depreciated) is:

- Cost basis: $50,000

- Less: Salvage value: ($8,000)

- Depreciable basis: $42,000

Using straight-line depreciation, the annual depreciation expense would be:

- $42,000 ÷ 5 years = $8,400 per year

Over the 5-year period:

- Total depreciation recognized: $42,000

- The truck's book value at the end of year 5: $8,000 (the salvage value)

What happens next?

When the company disposes of the fully depreciated truck after 5 years:

- If they sell it for $8,000 → no gain or loss

- If they sell it for $10,000 → $2,000 gain on disposal

- If they sell it for $6,000 → $2,000 loss on disposal

A key point: The salvage value of $8,000 was never depreciated. Only the $42,000 difference between the original cost and the expected residual value was expensed over the asset's useful life.

GAAP requires salvage value consideration for straight-line depreciation and other book depreciation methods. Conservative estimates recognize that most assets have minimal salvage value after full useful lives.

Tax depreciation under MACRS ignores salvage value completely. The IRS allows businesses to depreciate full cost basis regardless of expected residual value. This simplification eliminates salvage value judgment calls for tax purposes. Businesses depreciate 100% of cost basis over MACRS recovery periods.

Key Note: GAAP depreciation stops at estimated salvage value. Tax depreciation continues to zero basis. The difference creates deferred tax assets or liabilities depending on whether book or tax depreciation is higher.

Depreciation Methods Explained

Four primary depreciation methods serve different business purposes and comply with different regulatory requirements.

- Straight-line depreciation provides consistency and simplicity.

- Accelerated methods like declining balance front-load deductions.

- Units of production ties depreciation to actual usage.

- MACRS depreciation determines tax treatment for most assets.

Let’s go through each of these in detail.

Straight-Line Depreciation Method

Straight-line depreciation allocates equal depreciation expense amounts across each year of an asset's useful life. This method provides predictable annual expenses and simplifies financial forecasting. Most organizations use straight-line depreciation for GAAP financial reporting because it reflects steady economic consumption patterns.

How Straight-Line Works

The straight-line method divides depreciable basis by useful life in years. The result is annual depreciation expense remaining constant throughout the asset's service life. This equal allocation creates stable expense recognition matching typical asset usage patterns.

Monthly straight-line depreciation equals annual depreciation divided by 12. Organizations recording depreciation monthly multiply the monthly rate by months in service during each period. Partial-year depreciation in acquisition and disposal years reflects actual months of asset use.

When to Use Straight-Line

Financial reporting under GAAP typically uses straight-line depreciation unless another method better represents actual economic consumption. The consistent expense pattern avoids earnings volatility from depreciation method changes. Public companies prefer straight-line for financial statement predictability.

Assets providing equal benefits each year suit straight-line depreciation perfectly. Office buildings, furniture, fixtures, and equipment used steadily throughout useful lives depreciate appropriately using straight-line methods. Assets without significant productivity decline over time match straight-line assumptions.

Formula and Example

Annual Depreciation = (Cost Basis - Salvage Value) / Useful Life

Example: A company purchases manufacturing equipment for $100,000. Installation costs add $5,000 to cost basis. Estimated useful life is 10 years. Expected salvage value is $15,000.

Depreciable Basis = $105,000 - $15,000 = $90,000

Annual Depreciation = $90,000 / 10 years = $9,000 per year

The company records $9,000 depreciation expense annually for 10 years. After 10 years, accumulated depreciation totals $90,000. Net book value equals salvage value of $15,000.

Declining Balance Depreciation Method

Declining balance depreciation accelerates depreciation expense recognition in early asset years. Higher initial depreciation better matches rapid economic value declines for assets losing utility quickly. The method applies a constant depreciation rate to declining net book value each year.

Understanding Declining Balance

Declining balance methods multiply a fixed percentage by the asset's current book value to calculate annual depreciation. Because book value decreases each year, depreciation expense decreases over time. This acceleration front-loads tax deductions and matches revenue patterns for assets generating higher returns when new.

The depreciation rate under declining balance methods exceeds straight-line rates significantly. Common implementations include 150% declining balance and 200% declining balance. Higher rates create more aggressive acceleration in early years, maximizing upfront tax benefits.

Double Declining Balance Method

Double declining balance uses twice the straight-line rate. For an asset with 10-year useful life, the straight-line rate is 10% annually. The DDB rate is 20% annually applied to remaining book value. DDB depreciation produces the most aggressive acceleration among common declining balance methods.

Assets depreciate fastest in year one, with depreciation decreasing each subsequent year. This pattern suits technology and equipment experiencing rapid obsolescence or performance degradation. Organizations often switch to straight-line depreciation when that method produces higher annual amounts.

Formula and Example

Annual Depreciation = Book Value × (2 / Useful Life)

Example: Equipment costs $50,000 with 5-year useful life and $5,000 salvage value. The straight-line rate is 20%. The DDB rate is 40%.

*Adjusted to reach salvage value

Total depreciation across five years equals $45,000. The accelerated pattern front-loads $20,000 in year one compared to $9,000 annually under straight-line depreciation.

Units of Production Depreciation Method

Units of production depreciation ties expense recognition directly to asset usage. Instead of time-based allocation, this method depreciates based on units produced, hours operated, or miles driven. Annual depreciation fluctuates with production levels, matching expense to actual economic consumption.

How Units of Production Works

The units of production method divides depreciable basis by estimated lifetime production capacity. This creates a per-unit depreciation rate. Each period's depreciation equals actual units produced multiplied by the per-unit rate. Heavy usage years generate higher depreciation naturally.

This approach requires tracking actual usage throughout asset life. Organizations must implement systems capturing production volumes, operating hours, or other usage metrics. Manufacturing equipment might track units produced. Delivery vehicles track miles driven. Rental equipment tracks rental days.

Best Use Cases

Manufacturing equipment with variable production volumes suits units of production depreciation perfectly. Equipment producing 10,000 units one year and 5,000 units the next should reflect this usage difference. Time-based depreciation methods fail to match expense with actual revenue generation patterns.

Mining and natural resource extraction use units of production matching depletion with resource extraction rates. Oil wells, quarries, and timber operations depreciate equipment based on resource units extracted. This aligns depreciation with revenue recognition as resources are sold.

Vehicle fleets benefit from mileage-based depreciation. Delivery trucks driven 50,000 miles annually depreciate faster than trucks driven 20,000 miles. Usage-based depreciation reflects actual wear and tear better than time-based methods for transportation equipment.

Formula and Example

Depreciation per Unit = (Cost - Salvage) / Estimated Lifetime Units

Example: A delivery truck costs $60,000 with $10,000 salvage value. Expected lifetime mileage is 250,000 miles.

Depreciation per Mile = ($60,000 - $10,000) / 250,000 = $0.20

Year 1 (45,000 miles): 45,000 × $0.20 = $9,000

Year 2 (52,000 miles): 52,000 × $0.20 = $10,400

Year 3 (38,000 miles): 38,000 × $0.20 = $7,600

Depreciation varies with actual usage, providing accurate expense matching. This method prevents over-depreciation when assets sit idle and ensures full depreciation when usage exceeds expectations.

MACRS Depreciation System

MACRS depreciation determines tax treatment for most business assets placed in service after 1986. The IRS mandates MACRS for federal income tax purposes. This system uses declining balance methods switching to straight-line, pre-determined recovery periods, and specific conventions for partial-year depreciation.

What is MACRS?

The Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System replaced previous depreciation methods with simplified property classifications and recovery periods. MACRS eliminates salvage value considerations and uses standardized depreciation tables. Businesses depreciate 100% of cost basis over mandated recovery periods regardless of actual useful life.

MACRS serves tax purposes exclusively. Financial reporting under GAAP uses separate depreciation methods and useful lives. This creates book-tax differences requiring deferred tax accounting. Organizations maintain dual depreciation schedules tracking both GAAP and MACRS depreciation for each asset.

MACRS Property Classes

MACRS Calculation

MACRS depreciation tables published by the IRS provide annual depreciation percentages for each property class. These tables incorporate declining balance methods, mid-year or mid-quarter conventions, and automatic switching to straight-line depreciation. Businesses simply multiply cost basis by the table percentage for each year.

The half-year convention assumes all property placed in service during a year was placed in service mid-year. The first year receives half the normal depreciation. The final year also receives the remaining half. This simplification eliminates tracking actual in-service dates.

Mid-quarter convention applies when more than 40% of annual depreciable property acquisitions occur in the fourth quarter. This prevents year-end tax planning timing all asset purchases in December. Under mid-quarter convention, assets placed in service during each quarter receive depreciation based on quarterly mid-point placement.

Example: A business purchases computer equipment for $10,000, classified as 5-year property using half-year convention and GDS 200% declining balance table:

Total depreciation equals $10,000 across six years. Note that 5-year property actually takes six calendar years due to half-year convention.

Section 179 Deduction and Bonus Depreciation

Section 179 deduction and bonus depreciation provide immediate expensing alternatives to traditional depreciation schedules. These provisions allow businesses to deduct full or partial asset costs in the year of acquisition rather than spreading deductions over recovery periods. Strategic tax planning requires understanding how these provisions work and their limitations.

What is Section 179?

Section 179 allows businesses to immediately expense qualified property costs up to annual dollar limits. Instead of depreciating equipment over five or seven years, businesses deduct the entire cost in year one. This provision incentivizes small and medium-sized businesses to invest in equipment, software, and certain property improvements.

Qualified Section 179 property includes tangible personal property used in business operations. Manufacturing equipment, computer systems, office furniture, and vehicles all qualify. Off-the-shelf software purchased for business use qualifies. Certain building improvements including HVAC, fire protection, alarm systems, and roofing also qualify under recent expansions.

Section 179 Limits for 2025

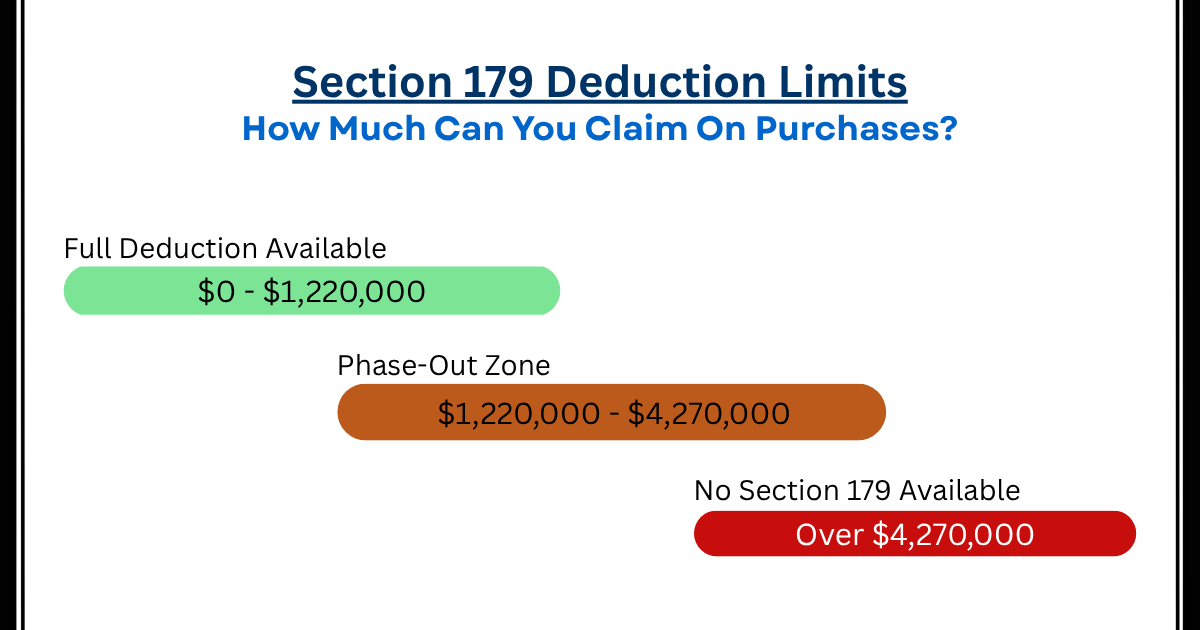

The 2025 Section 179 deduction limit is $1,220,000 for qualified property placed in service during the tax year. Businesses purchasing up to this amount in qualifying assets can expense the entire cost immediately. This limit applies per business entity, not per asset.

Phase-out threshold of $3,050,000 reduces available Section 179 deductions dollar-for-dollar once total equipment purchases exceed this amount. A business purchasing $3,200,000 in qualifying property during 2025 would reduce their Section 179 limit by $150,000. Purchases exceeding $4,270,000 eliminate Section 179 eligibility entirely.

Taxable income limitation prevents Section 179 deductions from creating or increasing net operating losses. Available Section 179 deductions cannot exceed business taxable income before the deduction. Unused Section 179 amounts carry forward indefinitely to future tax years with sufficient income.

Understanding Bonus Depreciation

Bonus depreciation allows businesses to immediately deduct percentages of qualified property costs in addition to regular depreciation. Unlike Section 179 with dollar limits and income limitations, bonus depreciation has no maximum deduction amount or taxable income restrictions. Businesses can create or increase net operating losses using bonus depreciation.

Qualified property eligible for bonus depreciation includes most tangible personal property with MACRS recovery periods of 20 years or less. New and used property both qualify under current rules. Computer equipment, machinery, furniture, and most business equipment qualifies.

The bonus depreciation percentage for property placed in service during 2025 is 40%. This represents another step down from 60% in 2024 following Tax Cuts and Jobs Act phase-out schedules. The percentage continues declining to 20% in 2026 before eliminating completely in 2027.

Strategic Considerations

Use Section 179 first for most small to medium-sized businesses. Section 179 provides immediate 100% expensing up to dollar limits, while bonus depreciation only provides partial immediate deduction. Section 179 also allows selective asset-by-asset elections while bonus depreciation applies to entire property classes.

Organizations expecting higher future tax rates benefit from accelerating deductions through Section 179 and bonus depreciation. Locking in deductions at current rates provides tax savings when future rates increase. Businesses anticipating lower future rates might prefer spreading depreciation over time.

Capital-intensive businesses exceeding Section 179 phase-out thresholds rely primarily on bonus depreciation. Organizations purchasing millions in equipment annually phase out of Section 179 eligibility but retain full bonus depreciation benefits. These businesses maximize tax deferral through bonus depreciation.

Depreciation in Different Industries

Asset depreciation requirements vary significantly across industries.

Manufacturing operations face different challenges than healthcare organizations. Real estate investors follow distinct rules from technology companies. Understanding industry-specific considerations ensures accurate calculations and optimal tax treatment.

Real Estate and Property

Commercial real estate depreciates over 39 years using straight-line methods for tax purposes. Residential rental properties use 27.5-year recovery periods. These long depreciation schedules reflect IRS assumptions about building useful lives, though actual economic lives often extend beyond these periods.

Cost segregation studies break building costs into components with shorter recovery periods. HVAC systems, electrical wiring, plumbing, and specialized lighting may qualify for 5-year, 7-year, or 15-year classifications instead of 39-year building treatment. Accelerating these deductions significantly improves early-year cash flow.

Qualified improvement property placed in service after 2017 receives 15-year treatment with bonus depreciation eligibility. This substantially improves deduction timing versus 39-year schedules. Real estate professionals benefit from cost segregation and accelerated depreciation more than other industries.

Manufacturing Equipment

Manufacturing companies maintain extensive machinery and equipment portfolios requiring complex depreciation tracking. Production equipment, assembly lines, robotics, and specialized machinery all depreciate under different classifications and schedules. Accurate tracking ensures maximum tax deductions while maintaining financial statement accuracy.

Production equipment typically falls into 7-year MACRS property classes. CNC machines, injection molding equipment, and assembly line components use these recovery periods. Some specialized manufacturing equipment qualifies for 5-year treatment depending on industry and equipment specifications.

Units of production depreciation works well for manufacturing assets when production volumes vary significantly. Component depreciation allows manufacturers to separately depreciate major equipment parts with different useful lives. Making distinctions between maintenance and capital improvements correctly prevents audit adjustments.

Technology and Software

Technology assets depreciate rapidly reflecting quick obsolescence cycles. Computer equipment, servers, networking infrastructure, and peripherals typically use 5-year MACRS recovery periods. Many organizations replace technology assets before full depreciation, creating disposal losses that provide additional deductions.

Software depreciation depends on whether businesses purchase or develop applications. Off-the-shelf software purchased for business use qualifies for Section 179 immediate expensing or 3-year amortization. Custom-developed software capitalizes and amortizes over longer periods.

Cloud-based software subscriptions don't depreciate at all. These operating expenses deduct currently as incurred. The shift from perpetual licenses to subscription models changes tax treatment from depreciation to immediate expense recognition. This affects cash flow timing and requires different tax planning approaches.

Vehicle and Fleet Depreciation

Fleet depreciation presents unique challenges combining mileage tracking, luxury vehicle limitations, and heavy vehicle advantages. Transportation-dependent businesses require sophisticated systems tracking individual vehicle depreciation and optimizing tax treatment based on vehicle classifications.

Standard automobiles face luxury vehicle depreciation limitations. For 2025, first-year depreciation including Section 179 cannot exceed $28,900 for passenger vehicles. Vehicles exceeding 6,000 pounds gross vehicle weight escape luxury limitations, qualifying for full Section 179 and bonus depreciation.

Mileage-based depreciation using units of production methods matches depreciation to actual vehicle usage. Fleet vehicles require tracking business versus personal use percentages. Detailed mileage logs substantiating business use percentages become essential during audits.

Common Depreciation Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Depreciation errors cost businesses thousands in lost deductions and create audit exposure. Most mistakes stem from poor documentation, incorrect assumptions, or outdated processes that don't scale with growing asset portfolios.

Recognizing common pitfalls helps finance teams implement controls preventing these issues.

Incorrect Useful Life Estimates

Useful life estimates directly determine annual expense amounts over asset service periods. Overestimating useful life understates annual expenses and overstates asset values. Underestimating spreads costs too quickly, potentially requiring adjustments when assets remain productive beyond estimated lives.

Lack of supporting documentation for useful life choices creates audit problems. Organizations must document why they selected specific periods using industry norms, manufacturer specifications, and historical experience. Without documentation, auditors question estimates and may impose their own judgments.

Failing to distinguish between economic useful life for financial reporting and tax recovery periods causes confusion. GAAP allows judgment-based estimates reflecting actual expected service lives. Tax law mandates specific recovery periods regardless of actual use.

Missing Depreciation Deductions

Assets placed in service but never added to depreciation schedules lose deductions permanently unless amended returns catch them within statute limitations. This happens frequently with small purchases falling through tracking cracks or major acquisitions where finance teams miss capitalization.

Inadequate capitalization policies lead to missed assets. When organizations lack clear thresholds for capitalizing purchases, employees expense items that should depreciate. Setting appropriate thresholds and training staff on application prevents this common error.

Purchase orders and invoices should trigger asset registration processes automatically. When procurement and accounting systems don't communicate, assets enter facilities without entering accounting records. Integration between systems or manual verification processes catch these gaps.

Poor Record-Keeping Practices

Inadequate documentation supporting cost basis, placed-in-service dates, and asset locations creates problems during audits and disposals. When selling or scrapping assets, businesses must remove specific items from records. Without accurate tracking, identifying which assets were disposed becomes guesswork.

Spreadsheet-based systems break down as asset counts grow. Manual updates miss changes when equipment moves between locations or transfers between departments. Version control issues create confusion about which schedule contains current information. Missing source documents during audits forces reconstructing cost basis.

Ghost assets—items fully depreciated or disposed but remaining on books—overstate asset balances and continuing depreciation. Regular physical inventories comparing actual assets to recorded items identify discrepancies. Disposal procedures should require accounting notification ensuring timely removal from records.

Failing to Update Depreciation Schedules

Asset circumstances change requiring schedule adjustments. Useful life revisions, impairment losses, and major improvements all necessitate recalculating remaining depreciation. Organizations that establish schedules at acquisition but never revisit them miss these required updates.

Impairment losses occur when asset carrying values exceed recoverable amounts. Economic changes, technology shifts, or physical damage trigger impairment testing. When impairment exists, reducing asset basis and adjusting future depreciation prevents overstated asset values on balance sheets.

Regulatory changes affecting recovery periods or bonus depreciation percentages require updating calculations for recently acquired assets. Organizations must monitor tax law changes and apply new rules to qualifying assets. Dedicated systems track these changes automatically rather than relying on manual monitoring.

Depreciation Red Flags Checklist

Best Practices for Managing Fixed Asset Depreciation

Effective depreciation management requires documented policies, robust systems, and regular reviews ensuring accuracy. Organizations implementing these practices minimize errors, optimize tax positions, and maintain audit-ready documentation. Best practices scale with company growth while maintaining fundamental principles.

Implementing a Depreciation Policy

Written policies establish consistent treatment across the organization. The policy should define capitalization thresholds, useful life guidelines by asset category, salvage value estimation methods, and depreciation method selection criteria. This documentation demonstrates control to auditors and provides guidance for staff.

Capitalization thresholds balance precision with practicality. Setting thresholds too low creates excessive tracking burdens for immaterial items. Most organizations use $2,500 to $5,000 limits for individual items. Useful life tables standardizing estimates by asset type ensure consistency.

Depreciation method selection guidelines explain when to use straight-line versus accelerated methods or units of production. Financial reporting typically uses straight-line for predictability. Tax reporting follows MACRS requirements. The policy should clarify decision criteria for situations allowing choices.

Maintaining Accurate Asset Records

Comprehensive asset registers serve as subsidiary ledgers supporting financial statement balances. Each record should capture acquisition date, cost basis including all capitalized amounts, asset location, responsible custodian, depreciation method, useful life, salvage value, and accumulated depreciation.

Unique asset identifiers enable tracking throughout asset lifecycles. Barcode tags or QR codes attached to physical assets link to database records. Mobile apps scanning identifiers during physical inventories verify existence and location, identifying missing items or recording relocations.

Physical inventories comparing actual assets to recorded items should occur annually at minimum. High-value or portable assets warrant more frequent verification. Change management processes ensure records reflect reality when assets transfer between departments or locations.

Regular Depreciation Schedule Reviews

Quarterly reviews ensure calculations remain accurate and current. Finance teams should verify depreciation expense appears reasonable relative to asset additions and disposals during the period. Unusual variances warrant investigation identifying calculation errors or missed transactions.

Reconciliation to general ledger confirms subsidiary schedule totals match control accounts. Accumulated depreciation and fixed asset balances should agree between detailed schedules and financial statements. Year-end review processes prepare for audits and tax returns by verifying all calculations follow current rules.

Technology updates and process improvements should follow each review cycle. If reviews identify recurring issues, implement procedural changes preventing recurrence. Continuous improvement maintains accuracy as operations evolve and asset portfolios grow.

Using Technology to Track Depreciation

Manual processes fail as asset counts grow beyond hundreds of items. Cloud-based platforms provide accessibility for distributed teams with automatic backups preventing data loss. Automated calculations eliminate formula errors plaguing spreadsheets by applying correct depreciation methods consistently.

Workflow automation routes new asset approvals, useful life revisions, and disposal authorizations to appropriate approvers. Audit trails document who made changes and when, providing accountability. Mobile capabilities enable field teams to conduct inventories using smartphones with real-time synchronization.

How Fixed Asset Depreciation Software Simplifies Management

Dedicated fixed asset depreciation software transforms depreciation from a monthly burden into an automated process requiring minimal manual intervention. Organizations managing hundreds or thousands of assets cannot maintain accuracy without purpose-built systems.

The right platform eliminates calculation errors, ensures tax compliance, and speeds month-end close.

Benefits of Automated Depreciation Tracking

Automated systems calculate depreciation across all assets simultaneously in seconds. Month-end processes that took days in spreadsheets complete in minutes. Freeing finance team time enables focus on analysis rather than calculation mechanics.

Dual-book tracking for financial reporting and tax purposes happens automatically. Systems maintain separate depreciation schedules for GAAP and IRS treatment without manual calculations.

Multi-jurisdiction calculations apply state-specific modifications automatically, handling Section 179 addbacks and bonus depreciation adjustments across states.

Real-time visibility into asset values, accumulated depreciation, and net book value supports decision-making throughout accounting periods. Managers access current data without waiting for month-end processing.

Tax planning scenarios model alternative depreciation strategies before filing, identifying approaches maximizing after-tax cash flow.

Key Features to Look For

Comprehensive asset tracking capabilities beyond depreciation distinguish robust platforms from basic calculators. The system should manage full asset lifecycles from acquisition through disposal including location tracking, maintenance history, and document storage.

Multiple depreciation methods including straight-line, declining balance, units of production, and MACRS ensure flexibility for different asset types. Unlimited depreciation books accommodate organizations needing separate calculations for federal taxes, state taxes, financial reporting, and internal management.

Automated tax calculations applying current-year Section 179 limits, bonus depreciation percentages, and MACRS tables eliminate manual lookups. The system should update when tax laws change rather than requiring user modifications. Customizable reports provide information in formats stakeholders need.

Integration capabilities connecting to accounting systems, ERP platforms, and procurement applications eliminate double entry. Automated data flows reduce errors and ensure consistency across systems. Dedicated technical support helps during implementation and ongoing use.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between depreciation and amortization?

Depreciation applies to tangible assets with physical form like equipment, vehicles, and buildings. Amortization applies to intangible assets lacking physical substance like patents, trademarks, and software licenses. Both allocate costs over useful lives, but terminology distinguishes asset types and different methods apply.

How do I know which MACRS property class applies to my assets?

IRS Publication 946 provides detailed property classifications with examples for each category. Most office equipment falls into 5-year or 7-year classes. Vehicles typically qualify as 5-year property. Buildings use 27.5-year or 39-year recovery periods depending on residential versus commercial use. When classification is unclear, consult tax advisors familiar with your industry.

Should I use the same depreciation method for financial reporting and taxes?

Not necessarily. GAAP financial reporting allows choosing methods that best reflect economic consumption, typically straight-line. Tax depreciation must follow MACRS rules providing accelerated recovery. Most organizations maintain separate depreciation schedules for book and tax purposes, requiring reconciliation but optimizing both objectives for better outcomes.

Can I change depreciation methods after I start using an asset?

Changing methods requires IRS approval through Form 3115 for tax purposes. GAAP allows method changes when new methods better represent consumption patterns, but changes require disclosure and justification. Arbitrary changes to manipulate earnings are prohibited. Most organizations maintain consistent methods throughout asset lives.

What records do I need to keep for depreciation purposes?

Maintain original purchase invoices, installation and setup cost documentation, placed-in-service date evidence, useful life estimation support, and depreciation calculation worksheets. Physical inventory records verifying asset existence and location support carrying values. Disposal documentation enables proper gain or loss calculation. Keep records for seven years minimum to satisfy IRS requirements.

Can I depreciate land improvements?

Yes, certain land improvements depreciate over 15-year periods under MACRS rules. Parking lots, fences, landscaping, and outdoor lighting qualify for depreciation deductions. Land itself never depreciates, but improvements adding value separate from land do qualify. Proper cost allocation between land and improvements ensures maximum deductions.

How does bonus depreciation differ from regular depreciation?

Bonus depreciation allows immediate deduction of a percentage of qualifying asset costs in the first year, supplementing regular MACRS depreciation on remaining basis. Regular depreciation spreads costs over recovery periods without first-year acceleration. Bonus depreciation has no dollar limits unlike Section 179, but both provide accelerated deductions improving cash flow.

Organizations managing 100 to 100,000+ assets trust Bassets for depreciation accuracy and efficiency. Our platform scales with your growth without migration projects or architectural changes.

Start with what you need today and expand when requirements grow without disruption.

.webp)